Sneak peek of the thing I've been writing

Gentle criticism only, please, I am a big sensitive baby.

(As I’ve mentioned here several times by now, I’ve been working on a book for the past year about mental illness in pop culture, and I’m currently about 75% through the first draft. Perhaps a bit presumptuously, I now share with you the introduction.)

I was 22 when Prozac Nation was published in 1994, only a few years younger than its author, Elizabeth Wurtzel, and several years deep into a battle with depression. Anxiety (not to mention as yet undiagnosed ADHD) had been with me for nearly my whole life, but this was something more insidious, a separate part of myself very intent on hurting the other parts.

An official diagnosis of depression wouldn’t come until 1998, but I had already been to a therapist twice as an adolescent, first because my parents were concerned that I was having trouble making friends, and then again later because they were concerned that I wasn’t processing their extremely acrimonious divorce. I didn’t mind it much the first time around, as the therapist was gentle and understanding, so gentle in fact that he would later play Jesus Christ Himself for several years in a local church’s Easter pageant. He mostly just let me sit in his office and read, which was what I liked to do more than anything.

The second therapist, however, took a sterner “I’m not here to take any of your guff, missy” approach, and all but demanded that we talk about the divorce, and how I felt about it. I refused to give in, though, answering most of his pointed questions with a shrug or some variation on “I don’t know,” or “I guess.” After a couple months of this, the therapist told my father (who was paying for these pointless sessions out of pocket) that he couldn’t help me because I wasn’t willing to open up to him. I felt oddly proud of this, like I was just too tough of a nut to crack, even though I desperately needed cracking.

Neither experience came close to addressing the growing sense of…well, for one thing, I couldn’t think of a word for it then. A journal I kept when I was 13 revealed both that I stayed up too late, and was convinced that everyone else was having a better time than me, both of which were habits I maintained well into adulthood. I was sad, I was angry, I was wracked with guilt over feeling sad and angry. I started sleeping a lot, crashing on the couch as soon as I got home from school and not getting up again until almost dinnertime. Though I wanted to be accepted by my peers, I also resented their seemingly carefree lives, and became more withdrawn from them. Every school year would start with my swearing it would be the year that things would change, that I’d somehow figure out how to be normal, and I always failed, and hated myself a little more for it.

But if you were to ask me how I felt then, I wouldn’t have been able to tell you. I couldn’t explain it in words.

Even when I entered adulthood, and finally had a taste of “normal” (friends, male attention, a modestly active social life), that sense of maybe it’d be better if I wasn’t here rarely left me. The only consolation was that a lot of people my age seemed to feel the same way. In fact, Generation X would become synonymous with “disaffected sadness,” even if we rarely spoke out loud about it.

Just the concept of Prozac Nation was exciting. Having been told that everything our parents used to numb their feelings – i.e. drinking, drugs, casual sex, etc. – was actually bad for you, we were frantically grasping for some sort of lifeline. Kurt Cobain, the official spokesperson for how shitty many of us felt, had already committed suicide earlier that same year. In the era before blogging and social media, to have someone, anyone write about what it was like to be “young and depressed in America” was a revelation, particularly when it was a peer, and not an “expert” offering empty advice or judgment.

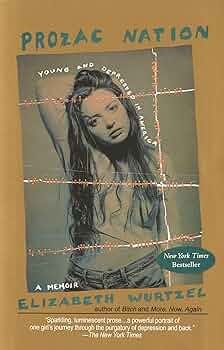

The “finally, a book for me!” excitement diminished as soon as I got a copy of it in my hands. First, there was the now-iconic cover, featuring a photo of Elizabeth Wurtzel as an alt-rock dream girl, right down to the artfully messy hair and cropped, perfectly flat belly exposing t-shirt. Her pose and pout suggested that someone could fuck the sadness out of her if they tried hard enough. That, plus the gritty stitches and sickly green art design made it look more like an advertisement for an underground record label rather than a memoir about depression.

I didn’t find much relatable on the inside either. My similarities with Wurtzel began and ended with sharing some of the same mental illnesses, and being of the same generation. She was beautiful, privileged, and well-educated, and her descriptions of weekend-long benders of casual sex and drugs sounded at least as decadent and glamorous as they were dangerous. I was not beautiful, or privileged, and I dropped out of college because I couldn’t afford it. More often than not, my benders involved gorging myself on junk food (and often vomiting it back up) and sleeping for twelve hours at a time. I didn’t land a job writing for The New Yorker and Rolling Stone at the tender age of 21, I was answering a switchboard for an Atlantic City casino, fielding calls from senior citizens seeking to cash in slot machine vouchers.

More than anything else, she just seemed to be trying too hard, going out of her way to convince her audience of how “different” she was. She claimed that, even as young as age 12, while other girls were listening to disco and giggling over boys, she was listening to the Velvet Underground and reading Sylvia Plath. It felt phony, performative, as if being mentally ill could be cool, somehow. I didn’t see it as Wurtzel merely “doing depression” differently than me, but better, in a way that people would find more interesting and, frankly, attractive.

That part turned out to be true, more or less. Whether intentionally or not, both the cover and the content of Prozac Nation heavily contributed to the grotesque stereotype of the beautiful woman whose emotional instability makes her sexually desirable. Sometimes she’s literally a murderer, other times just someone desperately in need of professional help, but either way her primary purpose is to shake up the life of some boring, normal schlub who finds himself drawn to her. She has no inner life, no identity beyond “crazy and sexy.”

While the “sad sexy baby” thing sold plenty of books, it didn’t do Wurtzel much good with critics, who blasted her “incoherent” writing (though it wasn’t any more incoherent than what professional Troubled Boy Jack Kerouac was celebrated for), and lack of filter. The Harvard Crimson (the paper of Wurtzel’s alma mater) described her as an “irritating, solipsistic brat,” and, like I did, disliked the memoir’s focus on sex and partying, rather than what it purported to be about. Ken Tucker of The New York Times wrote that the book would have been better if Wurtzel wasn’t so deeply impressed with herself, her accomplishments, and her own writing, as she compared her teenage poetry to the work of Plath and Djuna Barnes.

The response to 2001’s More, Now, Again, a sequel of sorts to Prozac Nation focusing on Wurtzel’s addiction to cocaine and Ritalin, was even harsher, with Peter Kurth of Salon even suggesting that the only thing that would make her writing interesting was if she died. Even though it became its own literary subgenre, critics and readers alike disapproved of Wurtzel’s freewheeling confessional style of writing. She was unapologetically messy, and despite describing all of her destructive behavior in excruciating detail, always seemed to come out on top, with another enviable writing gig, another chance, still an “it girl.” If these were supposed to be cautionary tales, then what were we supposed to learn here, other than what CDs are the best to cut lines of coke on?

Prozac Nation turned 30 years old in 2024. I reread it in preparation for writing this book, and I didn’t like it much better than the first time around. From a 21st century perspective, when people share descriptions of their hemorrhoid surgery on social media without prompting, Wurtzel’s recounting of one debauched experience after another was now boring and repetitive instead of shocking and titillating. But I also noted this time around that its focus on drug-induced decadence and rambling incoherence wasn’t all that different from the writing of Hunter S. Thompson, who somehow managed to escape the accusations of self-absorption and attention seeking. Nobody ever said he should have been a little more humble, or that he’d be a more interesting writer if he was dead.

30 years older myself, I was able to give Elizabeth Wurtzel the grace I couldn’t spare at age 22. Just because her version of depression was different than mine didn’t invalidate it. Beyond the cool girl posturing, there were some genuine moments of relatable insight, such as “That’s the thing about depression: a human being can survive almost anything, as long as she sees the end in sight. But depression is so insidious, and it compounds daily, that it’s impossible to ever see the end.”

It was bold to be unapologetic for her self-destructive choices, especially when most depressed people exist in a constant state of guilt for sins both real and imagined. I no longer blamed her for focusing too much on salacious details, or even for that seductive cover. Unpleasant subjects are often presented in a pleasing package so that people will pay attention to them, and Wurtzel was just using what God gave her as an advantage. It was uncharitable of me to think that because she was attractive and lived an exciting, privileged life she didn’t “deserve” to be unhappy.

Wurtzel, who died of cancer at just 52 in 2020, continued writing in the same disjointed, stream-of-consciousness style even after she got sober. She also continued to be kind of a mess, jumping from a writing career to a brief stint as a lawyer and then back to writing again, and struggling with bankruptcy, tax liens, an eviction, and accusations of plagiarism. A 2013 essay she wrote for New York magazine was more of the same: a long, unfocused recounting of her accomplishments and her sex and drug-driven foibles, and a desperate need to be perceived as different from other girls, even well into middle age. But there was a poignancy under the surface, as Wurtzel mourned her lost youth, and admitted that she was “alone in a lonely apartment with only a stalker to show for my accomplishments and my years.”

Mostly, she acknowledged that despite the success and fame (some would say infamy) Prozac Nation brought her, she wasn’t much happier than when she wrote it. She was honest: mental illness never goes away, not entirely. Pop culture would love to tell us differently: that all it takes is a change in circumstances, willpower, the right person to love us, etc., to cure our broken brains. At best, in reality, it lays dormant, in remission.

I don’t imagine Elizabeth Wurtzel intended to influence a negative stereotype about mentally ill women. It certainly wasn’t the first, last, or most harmful way to make mental illness palatable, more entertaining for an audience. But I would have liked to have known what she thought about it.

So I guess, in a way, this book is for her.

I’m hooked and ready to read more.

Love this. Go you good thing